Deposit Wars

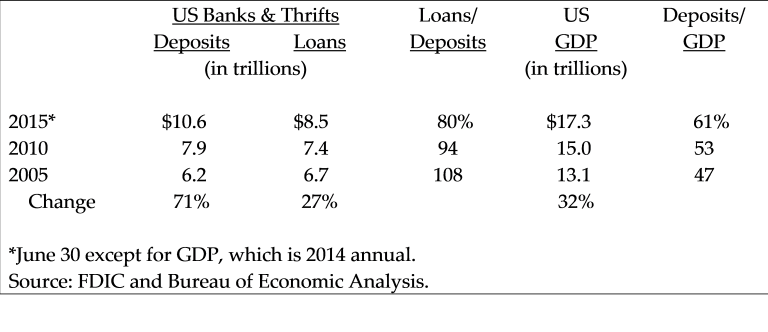

Deposits are the raison d’etre for the banking industry. The business exists to use the liquid savings of the nation productively. Whether used for commercial loans, housing or lending flows to be securitized, deposits provide stable, reliable and low cost funding. Given this the industry should be celebrating an amazing success. Since 2005 domestic US deposits have increased from $6 trillion to $11 trillion, or 71%. Over the same period the US economy measured by GDP has only grown 32%. Deposits to GDP have increased from 47% in 2005 to 61% in 2015.

The surge in deposits has not been matched by lending, which is up 27% for the ten year period, close to but lagging, the economy. One result is the loan to deposit ratio for the industry has declined from 108% in 2005 to 80% in 2015. Regulators consider this is a positive change increasing liquidity in the system.

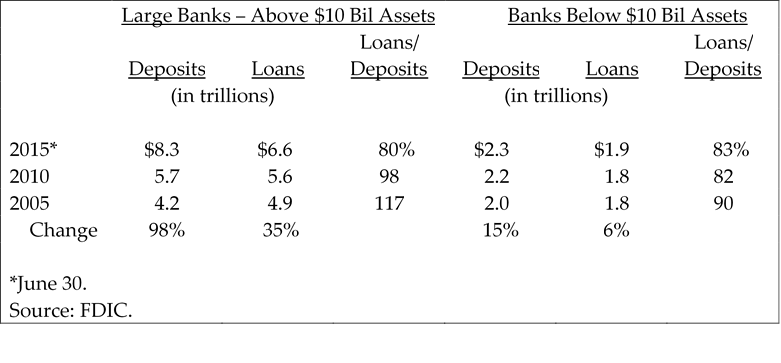

As might be expected, a closer look at the details reveals some ominous trends going on under the surface. The growth in deposits has accrued almost entirely to the large banks. If you split the banks by size, either above $10 billion in assets or below $10 billion assets then:

- Large bank deposit growth stands at $4.1 trillion and small bank growth at $300 billion. This is 98% growth vs 15% growth, respectively, over the 10 year period.

- Small banks, which controlled $1 of every $3 of deposits in 2005, now struggle to maintain $1 in $5.

- In the last ten years, large banks have attracted deposits equal to roughly twice the entire size of the small banks amount combined.

Given results like these, one might argue the deposit war is over. Large banks, which sat at the center of a credit crisis, have subsequently hoovered up unending liquidity. Small banks, hamstrung by the regulatory response to the credit crisis, have been withering.

Whenever Elizabeth Warren or a Federal Reserve Governor touts small bank friendliness, it’s hard to know whether to blanch at the naivete or shrink from what must be cold-blooded calculation. Wherever you put the blame, small banks have fewer deposits today on an inflation adjusted basis than ten years ago in spite a near doubling of the available pool.

To be fair there is controversy surrounding the deposit bonanza of the large banks. Many feel near zero interest rates have made other short term stores of liquidity unattractive. Money market funds, a primary alternative to bank deposits, have struggled from fallout from the credit crisis and subsequently from the impact of very low interest rates on the business model. Some analysts feel $1 trillion of deposits could melt out of the large banks even with a modest rise in rates.

Even so it is amazing to see the statistical change that has come to the bank deposit structure. Bank of America pays only about 8 basis points on its entire deposit base, whereas the average large community bank is paying somewhere around 50 basis points and small community banks are closer to 70 basis points. Another troubling reality for small banks, they pay more and get less. A quick look at the structure in the Washington area reveals a lot.

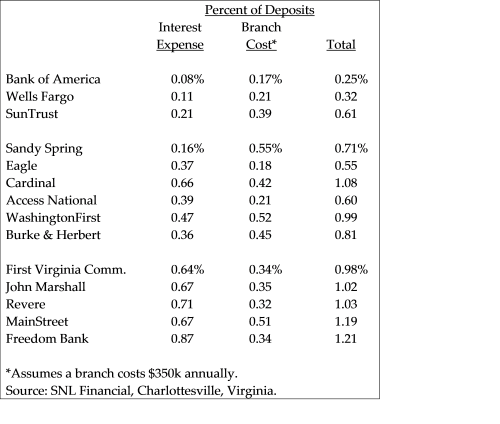

Deposits have two primary costs, the interest the bank must pay and the cost of the branch infrastructure to serve clients. Branch costs are not reported in bank financials, so to simplify things, it is assumed it costs $350 thousand annually for a branch. This includes the cost of the physical location and the people whose primary function is deposit services. Obviously this simplification isn’t perfect, but it does allow one to guess at which banks have built a durable cost advantage in deposit funding.

Using this approach, Bank of America pays 8 basis points for its deposits in interest expense and an estimated 17 basis points in direct costs, so total cost of deposits is 25 basis points or ¼ of one percent. Wells Fargo, another national bank, has similar numbers only slightly higher. SunTrust, which is a large bank but only 1/10 the size of Bank of America, pays a little more for its deposits and is less efficient per dollar of deposits, so its total cost is 61 basis points. A 30 basis point differential may not seem like much, but in banking it can make the difference between being mediocre and successful.

The community bank deposit cost structure is higher with more interest cost and more direct costs relative to the deposits attracted. There are some notable exceptions. Sandy Spring has low interest costs with above average direct costs, but the combined number is competitive. Eagle and Access National stand out with total costs below even SunTrust. A good portion of the return on equity difference between the high performing Access National and Eagle vs some of their peers can be traced to these deposit efficiency advantages.

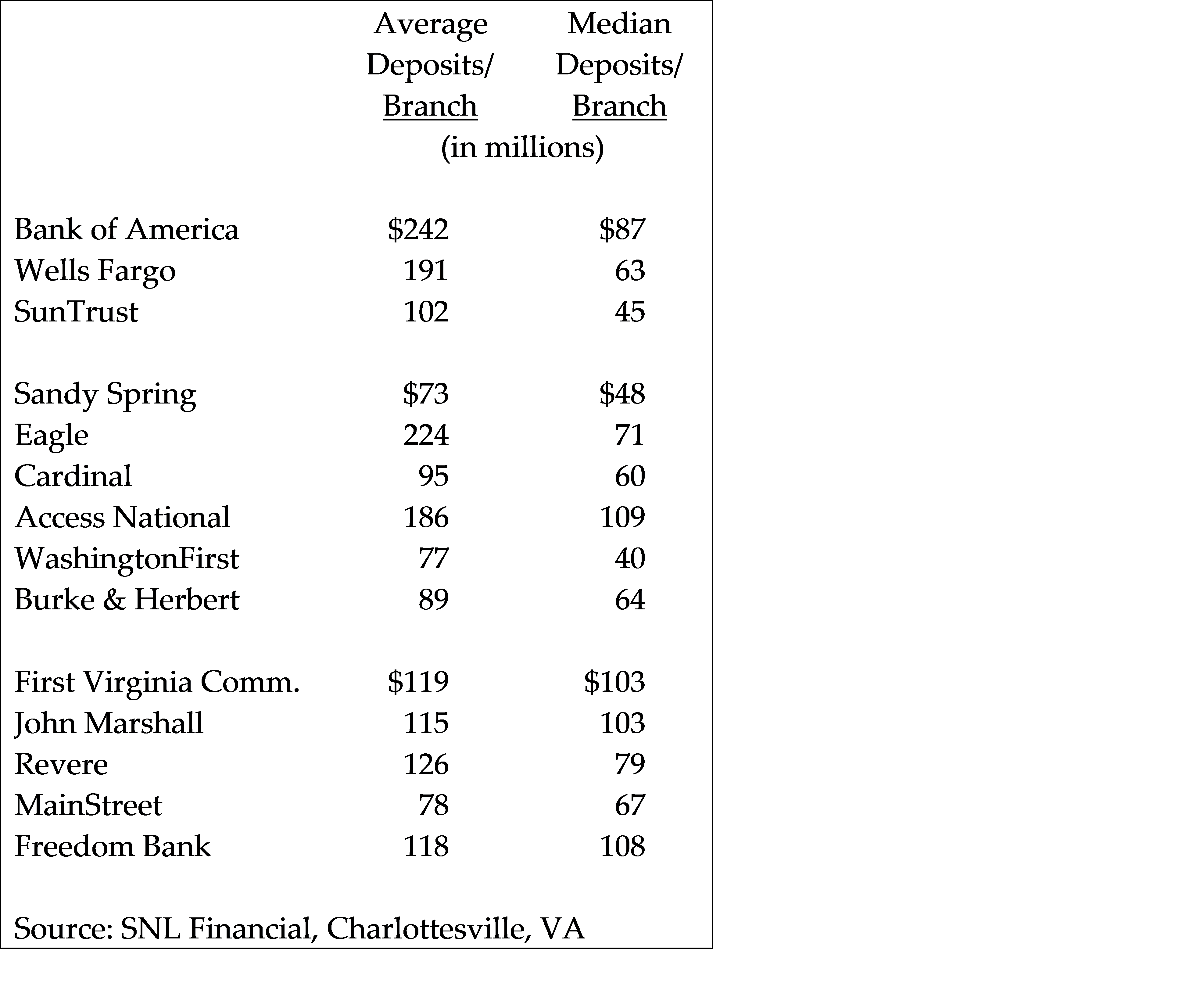

Another simple calculation at the bank franchise level is to look at average deposits per branch vs median deposits. At Bank of America the average is $242 million deposits per branch, about 3 times the median of $87 million. This is because a huge portion of Bank of America’s deposits are booked in massive headquarter branches and are not really “branch” tied deposits. More than half of large bank deposits likely have little need for the “nearby” branch.

Among the community banks only Eagle and Access National have achieved scale ratios similar to the large banks. Eagle’s average deposits per branch is $224 million while the median is $71 million, or very similar to the Bank of America ratio. It is reasonable to assert that a good portion of Eagle’s deposits are relational and not overly dependent on the immediacy of branch coverage. For smaller community banks there is little difference between median and average deposits per branch.

The overall implications of the deposit trends are far reaching. Half of the deposits of the nation may already be out of the reach of “branch based” thinking. The decision to keep a branch open will no longer be based on the size of the deposit base ascribed to a branch, but the much smaller amount of deposits at a branch where the customer actually cares that the branch is there.

The technology to serve clients by internet and mobile has been available for years. Obviously adoption of this technology is at the heart of the deposit market change. Nevertheless the change is profound and is being impacted by the short term economic reality of the last several years. Small banks have been forced to hunker down and limit growth, both because lending opportunities were scarce and regulators were imposing ever higher capital ratios. At the same time large banks, prodded by newly imposed liquidity ratios, have been aggressively gathering deposits. Whether this behavior was prescient, or just the result of being beaten like a dog, large banks have been successful in the deposit war. Given that deposit customers may be just as likely in the virtual world to be very sticky customers, deposit victories today might last decades.

The successful community banks of today likely point to the best strategic path. The relationship package that a community bank makes available to its community must be suitably broad to maintain relevance and scale. Fee services have been touted for years as necessary for community banks to earn a favorable return on equity. Increasingly they may be necessary to have the breadth of presence in a market to attract the necessary deposit funding for the lending line of business.

The view of scale also becomes more nuanced. Having a billion or even ten billion of assets may be less important to profitability than the amount of business being done relative to the infrastructure investment. Productivity per head and per location likely trumps total volume. Once again the local community banks that have achieved the same scale per office as the largest bank franchises appear the most successful in terms of bottom line performance. The cost benefit of branch scale likely flows through to price competitiveness allowing these companies to win business and make above average returns on a net interest margin too low for most local competitors.

In all industries there are inflection points where things start to move in a new direction. In banking we had one seven years ago, when interest rates crashed and stayed historically low. Those that saw the extended benign rate environment knew that the ability to generate productive assets would separate those that did well and those that did not.

Many have assumed that rising rates would be the new inflection point returning us to “normal”. Our belief is that the rate guessing game is a canard. Underneath a benign deposit cost environment, change has accelerated. In the next several years, rates may move up a little or a lot, but winning the deposit war will be the indispensable trick. Those that do will have the chance to achieve their goals, those that do not probably won’t be big enough for anyone to care.