Pig in a Poke

“Pig in a Poke” dates back five centuries and once meant purchasing a piglet in a sack sight unseen. It’s something two trusting business partners might do to save time. It has come to mean buying something without good knowledge or even worse, being scammed. Letting the cat out of the bag is the accompanying cliché. It is the scam being discovered at some point in the future.

Our feeling is that we are entering a “pig in a poke” stage for investment markets, which is something that happens during good times, when people are flush and everything is working. A good example is last year’s mega IPO – Uber. Uber is an exciting way to organize transportation. It is a network, a platform and a global business, which are sexy investment points that gloss over the facts that Uber loses money and has multiple international competitors. A deep dive into Uber’s bag of poorly written IPO prospectus documents came up whiskers, but many didn’t bother to look. Pig in a Poke.

This time last year Apple was available for $150 to $160 per share. Analysts said its best days were behind it because the replacement cycle for smart phones was getting longer and Apples’ newest products weren’t compelling. The stock traded at 12 times earnings, a low multiple for a tech company. Fast forward one year and Apple is at $317 per share and 27 times earnings. Analysts are crazy about the 5G replacement cycle and how big the profits might be. Apple has a long, prosperous future, but as a starting point for new investment, now doesn’t seem very attractive.

Apple’s price isn’t the problem. People are going to use Apple’s recent performance history and obscure it. Funds and ETFS will tout low fees and high returns to attract investment dollars, but when you look under the hood, 30% or more of the fund will be Apple and other mega techs. The high recent returns are just Apple running from $150 to $300. Many won’t check the details and will hope their new fund can just do what it did last year, but who would bet on Apple going to $600 and 40 times earnings? Pig in a Poke.

The economy is strong with near full employment. The Chinese trade deal and Fed Rate cuts will provide stimulus in 2020. Money from profits, investment gains and wages is finding its way into real estate and equity markets. The people directing this money are feeling good and smart. Almost all investment strategies worked last year, and people love to repeat what has worked in the past. They will even add leverage.

Peter Lynch, the famous manager of the Magellan Fund in the nineties, offered a pithy image of high-priced markets as a crowd in front of most stocks. The crowd doesn’t make the companies the stocks represent bad, it just makes buying them more expensive. It’s the crowd, of course, that attracts pig salesman. Peter’s advice, we are sure, would be to go look for something that isn’t crowded.

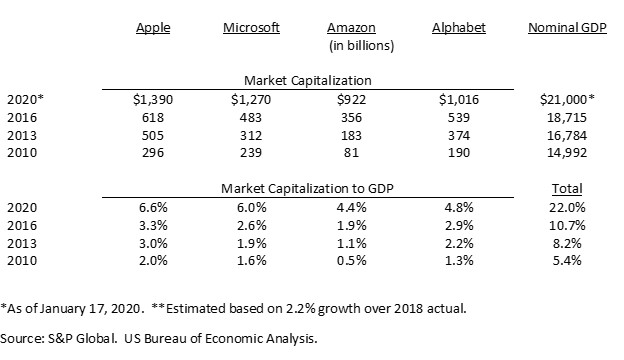

Let’s look at the four juggernauts of our time – Apple, Microsoft, Amazon and Alphabet (Google). Apple, Alphabet and Microsoft have surged to market capitalization above $1 trillion each and Amazon is close to the trillion mark. Their combined market capitalization of $4.6 trillion is 22% of GDP. This is not a typical ratio to calculate, but it gives an idea of comparing wealth (market cap) to goods and services (GDP). Three years ago, these four companies had a market cap equal to 10.7% of GDP.

Consumers make up about 70% of GDP in the US. Almost all of us aren’t spending anything close to 10% to 20% of our money on these four companies. Their market cap is based on future growth expectations, because they are all trading at 4 to 10 times revenue. You can’t eat Apple and Amazon doesn’t build houses. If markets and liquidity tighten up, a lot of people will want to sell to tide themselves over in the basic needs department.

There is another problem. As great as these companies are, history suggests they are not all going to meet expectations. Competitors will come along and take some of their business and profit margin. Technology will shift or consumer tastes will change. Performance won’t be as good as anticipated.

The last time the technology sector was a quarter of the market cap of the S&P 500 index (like it is now) was 1999. In that year the four largest market cap stocks were Microsoft, GE, Cisco and Exxon Mobil with market caps of $583 billion, $504 billion, $353 billion and $196 billion, respectively. Nominal GDP in 1999 was $9.6 trillion, making the combined market cap of the four largest companies 17% of GDP.

In 2020, Microsoft is a little more than double its 1999 market cap, which is a tortoise like 5% annual stock price increase over 20 years. Even that required great patience, because three years ago Microsoft was still below its 1999 high. General Electric, a triple A rated conglomerate in 1999 with a highly admired managerial system, turned out to be more like a hedge fund strung out on cheap financing. It has declined 80% since 1999 to a current market cap of $103 billion. Cisco was and is a good company, but it didn’t meet its lofty 1999 expectations. Its current market cap is $207 billion. Exxon Mobil is $100 billion higher in market cap now vs 1999 and has always paid lots of dividends. Still, over the last few years the bloom has come off the oil industry for investors with massive new supplies in the US coinciding with electrification and the green economy movement.

While skepticism about the price of Apple, Microsoft, Amazon and Alphabet in 2020 might be appropriate, the businesses are rock solid. Apple, Microsoft and Alphabet produce huge amounts of cash and carry negligible debt. Amazon is a poor earner, but it is not debt encumbered and it is single handedly demolishing retail in the US as we know it.

Peter Lynch didn’t shy away from high markets or low markets – there is money to be made in both. Price and future performance are simply variables in the investment equation. During periods when the general market moves strongly higher, like last year, it is relatively easy to get a good result and tempting to enjoy the ride. Flush investors anxiously add new money and lots of “deals” are on offer in a vibrant economy. It’s like walking out of the souk and into the opium market. An investor should react just as this unwary shopper should. Be careful and make your way back to the meat and potatoes.

We are reminded of an investment made in 2000, just as the Nasdaq was peaking for that generation. It was a recapitalization of a small bank that needed capital after suffering a fraud. The bank was bought out a few years later by a local competitor and for those of us who invested, the tech wreck was completely irrelevant. As it turned out, the bank sector overall performed very well between 2000 and 2002 even as the Nasdaq deflated. Fearing recession, Alan Greenspan aggressively lowered interest rates to avert recession and this made the banks attractive.

In 2020, history won’t repeat the events of twenty years earlier, but some of the patterns will. Strong markets paradoxically call for even greater investment discipline, otherwise there won’t be any bacon on your plate next summer.

Featured Image Credit: @koty_vezde