Trouble in the Oil Patch

This title is borrowed from a former partner, Arnold Danielson, who wrote a terrific history of modern American banking titled Consolidation of Banking. Arnie devotes a chapter to Texas between 1985 and 1989, when a drastic decline in the price of oil from $37 to $10 per barrel (73% decline) devastated the domestic oil and gas industry along with Texas real estate and banks. The recent decline in oil from about $115 in 2014 to about $30 today is a similar 74% decline. If you measure from the absolute peak of $145 in 2008, then the decline reached 80%.

The chapter begins with the history of an infamous, but very small Oklahoma bank, Penn Square Bank. Only about $500 million assets at its peak, Penn Square originated very large oil and gas credits and participated them around the country. Penn Square loans brought down the largest banks in Chicago and Seattle and even did considerable harm to Chase Manhattan. We are sure Seattle and Chicago investors were very surprised when their local banking leaders were destroyed by what were largely Texas and Oklahoma loans. Loan buyers failing to do their own due diligence was a primary contributor to the much more recent Great Recession.

The problem of hidden contagion haunts markets today. Fourth quarter earnings conference calls featured detailed questioning on oil and gas exposure for the large banks. So far the actual numbers don’t match the concern. JP Morgan put aside $150 million in the fourth quarter in anticipation of problems with energy credits and estimated $750 million of additional provisions if oil continued lower. The $150 million provision is 2% of JP Morgan’s fourth quarter pretax income. The total potential exposure compared to JP Morgan’s $175 billion of tangible common capital is an insignificant 0.4%. With the exception of a handful of regional banks in the oil patch, the same calculations will apply and little direct damage will accrue to our large banks from their portfolio of oil and gas loans.

Dismissing the potential direct losses from energy loans as minor doesn’t put the issue to rest, or to recall Jamie Dimon’s worst market comment – make it a “tempest in a teapot.” Returning to Danielson’s book, of the ten largest banks in Texas in 1984, seven failed, two were sold in distress and only one remains – Cullen Frost. Troubled energy loans didn’t kill those nine banks – real estate did.

Oil and gas extraction is a primary industry generating jobs and employment. When production contracts, like today, the direct and indirect losses can bring down an entire region’s economy. All of the estimates for losses given by the large banks include an estimate for how long oil is expected to “stay down”, ie. below $30 a barrel. “Lower for longer”, another new phrase cropping up, is the thought that oil might be in a malaise measured in years, not months. The length of time matters to banks because industries and regions under stress don’t dissolve instantly. Primary industry layoffs have only just begun and companies still haven’t exhausted their financial reserves. It will literally take years for the economic distress to cause the major real estate markets in oil country to seize up in a meaningful way, if it ever actually happens.

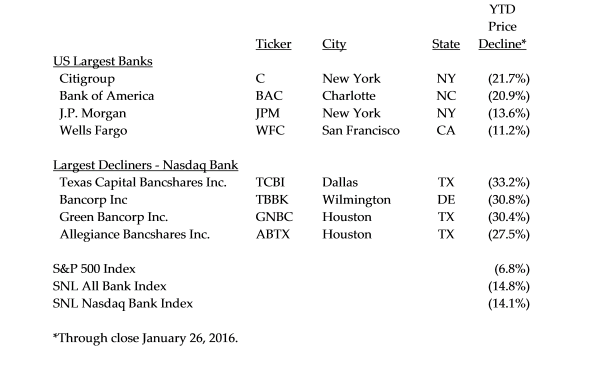

The real knock on large banks from the oil price crisis may be the cure, not the disease. Regulators will likely add draconian assumptions for the energy market to their 2016 “stress test.” Newly updated accounting guidelines force banks to reserve immediately for all potential losses even when there is great uncertainty. Citigroup and Bank of America have been the weakest performers in the January sell-off, and this might reflect the market’s expectation that the Fed will prevent both from increasing their payout ratios and buyback programs. Just when both companies should be aggressively acquiring their well below tangible book shares, the government is likely to say no or at least limit the amounts significantly. The regulators, not oil, are still the bigger worry for large bank valuation.

The Texas analogy of the eighties is probably more applicable when thinking about the rest of the world’s oil producing regions. The booming real estate and economies of the cities in Gulf countries seem very similar to the suddenly very overbuilt Texas markets of the eighties. The foray into expensive deep water drilling by Brazil’s Petrobras looks like a shaky house of cards. The bank failures that may occur in international markets could be pretty spectacular, but it is the early innings and months if not years will pass before banks and governments face up to the problem.

Here at home community bankers would do well to think carefully about the long term impact of low oil and low energy prices. The sudden troubles of a particularly egregious lender, Coastal Bank in Bradenton, Florida in December 2006, was an early canary in the coal mine relative to the oncoming 2008 housing led recession. This time it’s low profitability from energy and it will impact more than just drillers and pipelines. Add a strong dollar to the profile and it becomes clear that segments of manufacturing, agriculture and the associated real estate may struggle. Early engagement, additional collateral, government backed lending and building reserves are the prudent early response.

Crises based on a set of unbalanced commodities do not last long. Unlike the financial collapse in 2008, this is not about fraudulent securities sold as high quality fixed income to banks all over the world. This is a supply driven problem to be solved either when OPEC and Russia scale down production or the natural depletion of oil fields brings balance in the absence of new investment. Oil market analysts and executives see this as happening by late 2016. Results in January suggest the market is factoring a bad scenario of $10 to $20 a barrel and reassessing all asset classes in that light. Recovery will be slower as it will be months to see which oil scenario plays out.

Although pundits tie recent market declines to a declining global economic forecast, it’s probably far simpler. Oil “interests”, whether domestic or foreign, likely need to raise cash and one of the easiest ways to do this is to sell publicly listed stock. The failure of some exotic hedge fund strategies may be compounding the selling as are the trend following funds and macro hedge funds. The natural buyers for suddenly cheaper equities are the pension funds and other patient money, but these aren’t fast buck investors and will take their time especially since prices keep getting better.

During a correction, our focus is to insure we have sufficient cash to acquire more of our “undervalued” assets at low prices. We feel there is significantly more gain in having cash to fund the right opportunities than in gains generated strictly by shorting. We test and retest our portfolio metrics to insure the integrity of our portfolio. Investors lose money in downturns because they fail to add to their good positions. Fear and lack of liquidity cause more losses than poor judgment. The addition and acquisition is done progressively and with low margin.